Signed and dated lower right: Blanche C. Grant / 1920

The artist; [Possibly] Major Byron Parsons (1835-1935) [the artist’s maternal uncle], Evansville, Indiana, in 1921-35; Collection of Taunton High School, Taunton, Massachusetts, by 1976; Private collection, Taunton, Massachusetts, acquired in 1976 when the school was demolished; Private collection, Warwick, Rhode Island, acquired from the above, 2023.

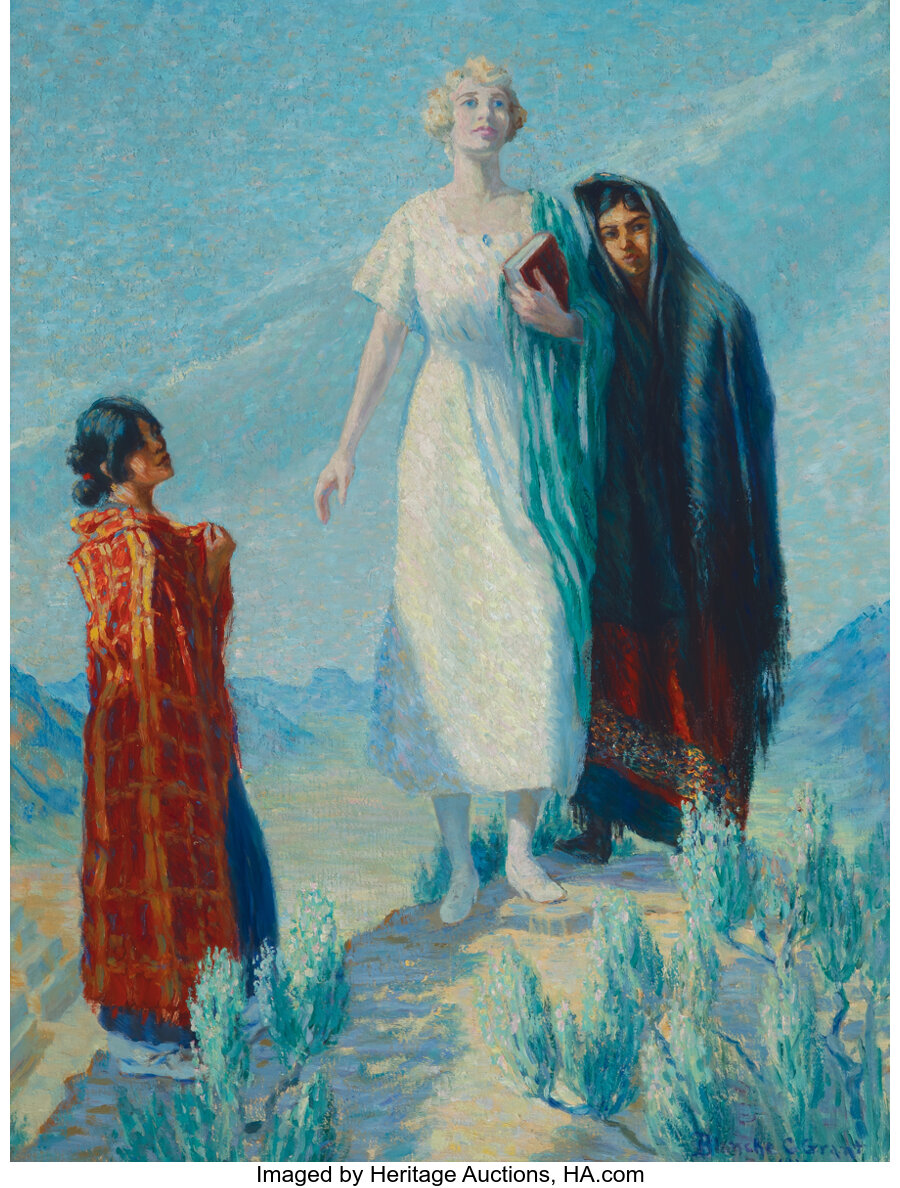

Blanche Chloe Grant (American, 1874-1948) Allegory of Suffrage and Education in Taos, New Mexico, 1920 Oil on board 40 x 30 inches (101.6 x 76.2 cm) Signed and dated lower right: Blanche C. Grant / 1920 Signed, dated, and inscribed on the reverse: B.C. Grant / Taos N.M. / 1920 PROVENANCE: The artist; [Possibly] Major Byron Parsons (1835-1935) [the artist's maternal uncle], Evansville, Indiana, 1921-1935; Collection of Taunton High School, Taunton, Massachusetts, by 1976; Private collection, Taunton, Massachusetts, acquired from the above in 1976 when the school was demolished; Private collection, Warwick, Rhode Island, acquired from the above, 2023. This large impressionistic scene of three women standing in solidarity against the backdrop of a New Mexican desert under a resplendent cerulean sky is a major rediscovery in the oeuvre of Blanche Chloe Grant, a painter, illustrator, teacher, and writer whose art and life were inextricably intertwined with the rich cultures and communities of Taos, New Mexico. Compositionally, the painting is designed in the manner of an altarpiece, with a large central figure on the highest ground, flanked by two smaller figures. The group is seen from a low vantage point, which conveys a sense of grandeur and seriousness to the scene. Sagebrush is blooming in the foreground at the women's feet while a view of the majestic Cerro Pedernal (colloquially known as Georgia O'Keeffe's mountain) recognizable by its distinctive flat top appears on the low horizon in the distance. The central figure is a willowy Anglo woman with short, cropped hair, signaling her unmistakable modernity. Her attire is all white from her short-sleeved, mid-calf length dress to her white stockings and white shoes—the universal "uniform" of the suffragette. As an accent she dons a shawl of bright green, a color prescribed by the suffragette community as appropriate for accessorizing since it symbolizes hope, as does the woman's aspirational gaze. She also holds a book against her chest—a mark of her allegiance to education—while marking two pages with her fingers as though she had just been reading from it to the women beside her. Suffrage and education, after all, go hand in hand. The woman on the left is likely from the Taos Pueblo while the figure on the right is more likely a representation of Hispana since she wears both a rebozo and an embroidered Spanish dress. In this image, Grant has united not only suffrage and education, but also indigenous Americans, Spanish-Americans, and white Americans. At the time it was painted, young unmarried white women were the largest teaching force in the United States as a whole, as well as in the non-white communities of New Mexico. Given the subject matter, date, and inscription ("Taos, NM 1920"), this colorful, uplifting work is very likely the first painting Blanche Grant made in Taos. It marks simultaneously a watershed moment for women in the United States and the start of a brand-new, exciting chapter in Grant's artistic life. Grant first visited Taos in early June of 1920, while on summer vacation from her teaching position as Associate Professor of Art at the University of Nebraska. She traveled there with Martha Turner, Nebraska State Historian. The two women stayed in Taos for a few weeks to make color sketches of the Indians and their surroundings. By July, Turner returned to Nebraska as planned, while Grant carried on with a previously planned trip to Laguna Beach, California. Quite taken with Taos, Grant soon expressed the desire to move there permanently and "blaze her own trail" as an artist. Letters flew between Grant and her maternal uncle, Major Byron Parsons, a Civil War veteran, an enormously successful owner of a grocery business in Evansville, Indiana, and a relative who had supported her ambitions to become an artist years before, when her own parents were skeptical of the profession. With her uncle once again ready to stand behind her, Grant resigned from the University. It is "with unbounded happiness," Grant wrote to Major Parsons, that she returned to Taos in mid-August 1920 with plans to stay permanently. At this time, the newspapers were reporting about the imminent passage of the Nineteenth Amendment [Women's Right to Vote], something for which Grant had long been a staunch advocate. It had passed Congress the year before, but was awaiting ratification, which finally took place on August 18, 1920, for white women. (Although the Indian Citizenship Act passed in 1924, finally granting citizenship and the right to vote to Native Americans, many states, including New Mexico, continued to restrict their access to the ballot.) Seizing the moment, Grant had her subject and began work on this painting. Telltale signs of the late summer season are embedded in the work from the suffragette's short sleeves, light fabric dress, and the blooming sagebrush. "Blanche Grant could really paint when she was hitting on all cylinders. This is a helluva painting!" wrote curator Michael Grauer of the National Cowboy Museum upon seeing this work through photographs shared recently with him (email correspondence dated January 31, 2024). "I also believe the white woman is allegorical to either suffrage or education. Things were very controversial in New Mexico at the time regarding assimilation, tribal lands, all kinds of things surrounding John Collier who would later become commissioner of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. It's a multilayered painting and one of the best and most complex by Ms. Grant that I have seen. A real treasure." In addition to the painting's intricate iconography, Grant's Allegory of Suffrage and Education in Taos, New Mexico is also a marvelous summary of the artist's educational, artistic and life skills to date. As a member of the first graduating class of Vassar College in 1896, where she majored both in English and History, Grant confidently took her knowledge of those fields into the profession of teaching. Directly after college, young Blanche Grant taught in the high schools of East Bridgewater and Taunton, Massachusetts, and later at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln. The shimmering impressionistic technique she used to render the radiant desert light in this work has roots in several aspects of her art training, including with Impressionist George L. Noyes who encouraged his pupils to paint outdoors in Annisquam; with Boston Museum School artists William McGregor Paxton and Philip Leslie Hale noted for the diffused light suffusing their figures in interiors; and with William Merritt Chase at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Her clear and legible composition is a testament to her exposure to the work of the great illustrator Howard Pyle through his students Ethel Pennewill Brown and Olive Rush in Wilmington, Delaware, as well as to her tenure working as a professional illustrator in New York. In Taos, Grant lived for 27 years in her studio home on La Loma, where her neighbors included W. Herbert Dunton, Leon Gaspard and her good friend Oscar E. Berninghaus. These years brought the opportunity to paint, win recognition, and send one-person shows to New York City. She exhibited with her peers on both the east and west coasts, including in "The First Traveling Exhibition of Western Painters." Besides her work as a painter, Blanche Grant flourished in Taos as a writer and historian, widely recognized in the field of Southwestern ethnology. Among her books are Taos Indians, Taos Today, Taos 100 Years Ago, When Old Trails Were New, Kit Carson's Own Story of His Life and Dona Loma. Her When Old Trails Were New published in 1934 contains an especially valuable art historical record of the nine Taos Society Artists who were living there at the time she first arrived in 1920. "Perhaps no better entertainment was afforded the Taos community than the historical pageants she planned and supervised," noted The Taoseño in its obituary of Grant published on its front page on June 24, 1948. "The first was in 1928, the covered wagons commemorating the trek of covered wagons over the Santa Fe Trail 100 years earlier." Her community involvement also included championing the organization of the city's First Volunteer Fire Department during the 1930s after a series of devastating fires. Following this success, she enlisted her many friends in the art colony to donate paintings for the purpose of raising funds for new space and firefighting equipment. Later still, she was involved in the effort to incorporate Taos as a municipality (1935), a move that provided the new fire department with running water. And to top it all off, Grant's effort to solicit paintings to raise funds ended up as a permanent art gallery that is still housed within the Taos Fire Department today. Owing to the generosity of the town, none of the originally donated paintings had to be sold, and together with the continuation of the tradition of donating works of art, the Taos collection now totals over 250 paintings by local artists. As a final tribute to the artist, the pallbearers at her funeral were among the city's luminaries: the Mayor of Taos, L. Pascual Martinez, and her friends Oscar Berninghaus, Victor Higgins, E. Martin Hennings and Lowell Cheetham. A few intriguing mysteries present themselves in the provenance of the work. One of them is whether Major Parsons purchased the painting from his niece. A newspaper article published in the January 9, 1921 issue of the Evansville Courier and Press, page 6, notes that the work was displayed in the private offices of her uncle's business (Scoville-Parsons Company) in Evansville in the days before it was heading to "the National Academy of Design, New York, for the Annual February art exhibit." Because it is not listed in the National Academy's exhibition record for 1921, the painting may have never left Evansville, having been purchased by Major Parsons for his own collection. It eventually became the property of Taunton High School in Massachusetts, the school where Blanche as well as her sister Pearl had both taught, beginning in 1901 following the death of their father. (Blanche's mother moved the family from Indiana to Taunton after her husband died, presumably to keep her family together because her daughters had found employment there.) Did Blanche donate the work to the high school, perhaps when it had come back into her possession following the death of her uncle in 1935? Or did it arrive in Taunton through another route? We are grateful to Michael Grauer for his suggested identification of the flanking figures in this work as Hispana and a woman from the Taos Pueblo. HID12401132022 © 2024 Heritage Auctions | All Rights Reserved

The painting is presented in its original frame.

Under UV exam, small 2 inch local area of scattered inpaint in the bottom right skirt of right figure. Three small dots of inpaint in the torso of the left figure, and two small dots of inpaint in the stomach of the far right figure. Small 1/4 inch dot of inpaint in the foreground lower right. The work has been recently cleaned and varnished.

A copy of the Las Negras Studio condition report is available upon request.

Framed Dimensions 49.5 X 39.5 Inches